The Legal Significance of Emojis in the Digital Age

The first documented “emoticon” use was in 1982: the function of writing ‘:)’ was to add emotional depth and nuance to a purely text-based message. Eventually, there was a shift from emoticons to emojis, graphic images that were code-based. First introduced in 1999, people used them in a similar manner to emoticons: to convey tone in written messages. Emojis, by themselves, are seemingly innocuous. Today, however, emojis have surpassed their use as “conveying tone” and are now often used as a form of communication, in and of themselves.

With the advent of email, text messages, and other forms of more informal communication, emojis have become ubiquitous. The 2016 Emoji Report found that “2.3 trillion mobile messages incorporated emojis in a single year,” and as of September 2021, there were 3,633 emojis in the Unicode Standard. When you add the frequency with which people use their phones to communicate about contracts and other important legal matters—let alone to sign said contracts—you’re left with the question: Should emojis have legal significance in the digital age?

Is There Research into Emojis and Their Legal Significance?

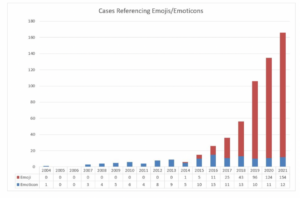

Because emojis are still so new, they are still being addressed in the legal system. The leading researcher on emoji case law is Eric Goldman, and according to his “2021 Emoji Law Year-in-Review,” there was a 23% increase (over 2020) in “court references to emojis and emoticons.” Reference the chart below (from his report) to see the growth of references to emojis over the past 17 years.

Goldman also authored “Emojis and the Law” (2018), one of the seminal research pieces on emoji use in case law. In his article, he delineates two main types of emoji-related legal issues. First, “emojis contribute to misunderstandings that will require judicial interpretation,” and second, they engender questions about how they are protected under intellectual property (IP) laws. One challenge with emoji misunderstandings is that recipients may not even see the same emoji on different platforms yet have no knowledge of this fact.

The bulk of his article is dedicated to looking at the intersection of those two ideas—how IP protection for specific emojis could help avoid misunderstandings.

More recently, in his 2021 Emoji Law Year-in-Review, Goldman notes that although courts use emoji evidence, they don’t have high regard for it. “Courts still denigrate emoji evidence. In Dean v. REM Staffing, 1:20-cv-00235 (N.D. Ill. May 10, 2021), the district court recounted how an email saying, “Yes, I accept. Dear [smiley],” formed a settlement agreement. The 7th Circuit affirmed the decision, but its opinion recaps the email as saying, “Yes, I accept”–leaving out the “dear” and the smiley, even though those components could have flipped the message’s meaning.”

Although there are numerous pop culture references to emoji and emoticon appearances in court cases, the most comprehensive (and accurate) resource remains Goldman’s research, both his 2018 article and his blog. He also stays abreast of current emoji research, such as this post which examines the Adobe 2022 Emoji Usage Trends survey.

There are also concerns about the trademark-ability of emojis and

What Have the Courts Said About Emojis and Emoticons?

Some definitive decisions, such as this one—which went to the Supreme Court—interpret single emojis or emoticons. Anthony Elonis, “who was convicted for using Facebook posts to threaten his ex-wife, has claimed that a threatening post toward her was clearly meant in “jest” because he included a smiley sticking its tongue out.” Although the emoticon was not the only evidence that the Supreme Court took into consideration, it was a component of the evidence that Elonis’ lawyer used to demonstrate that his threats were not serious.

Although this case didn’t occur in the United States, this chipmunk emoji case is possibly one of the best-known court cases. The case involved a couple looking to rent a house and a prospective landlord. The text message in question includes six emojis: a Spanish dancer, a woman with bunny ears, the V sign made with fingers, a comet, a chipmunk, and a bottle with a popping cork.

An Israeli small claims court decided, “ Although this message did not constitute a binding contract between the parties, this message naturally led to the Plaintiff’s great reliance on the defendants’ desire to rent his apartment. As a result, the Plaintiff removed his online ad about renting his apartment.” Although they agreed that it was not a contract, the court did decide that the defendants acted in bad faith in the negotiations.

What Are Some Recommendations for the Future?

According to Goldman, there are three helpful ways to clarify emojis in court cases. First, lawyers should use a depiction that matches exactly what their client saw. This helps address the concern that a sender and a recipient could be seeing different symbols, depending on their device, where they see the emoji, etc. Second, judges should include an image that matches the actual emoji in their court opinions when possible. Doing so would create a stronger reference base for future use. Finally, Goldman recommends that the actual emoji be displayed in court, in instances involving any read testimony, etc. They should not be orally described, as this can miss nuances.

It’s also critical to note that as emoji use continues to develop and mature, so too will its legal relevance. Does the “thumbs up” emoji indicate agreement and a binding contract? Does an emphasized exclamation point indicate excitement? These and other questions regarding contracts, trademarks, and more will continue to surface as emoji use increases even more.

In instances where a business is concerned about the implications of an emoji—or its interpretation—it’s important to speak with a California attorney who is well-versed in this specialized legal arena.